The term ‘the ton‘ referred to the elite of Regency society, a small, exclusive group of aristocrats and wealthy individuals who set the standards for fashion, behaviour, and social interaction. Being part of the ton was the ultimate mark of status, but it came with immense pressure to maintain one’s reputation. In this world, a single misstep could lead to social ruin.

What Was the Ton?

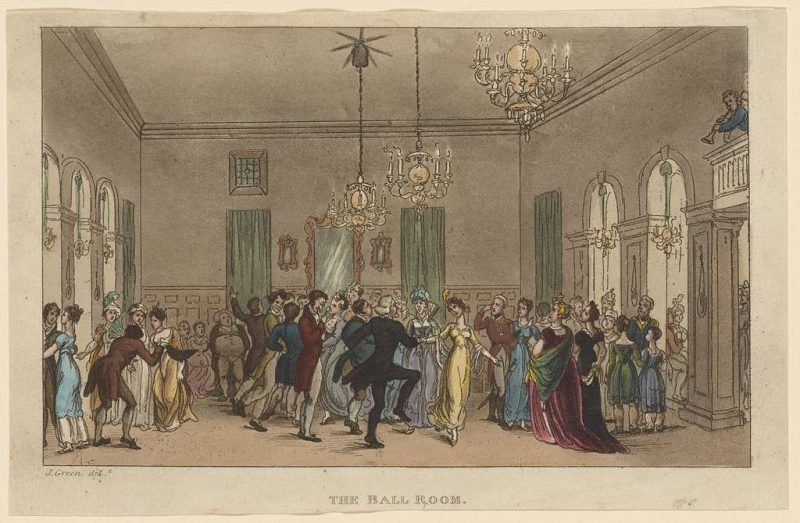

The ton was not a formal institution but rather an informal network of influential families and individuals. Membership was based on birth, wealth, and connections, and it was fiercely guarded. The London Season, a series of social events held each spring and summer, was the ton’s playground, where marriages were arranged, alliances formed, and reputations made or broken.

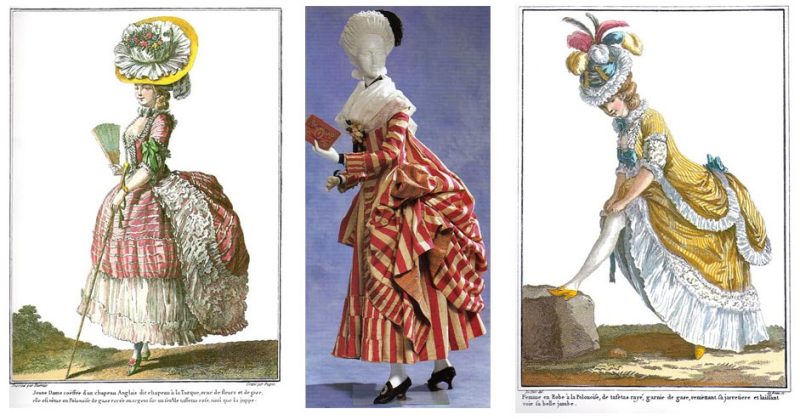

The term ‘ton‘ derived from the French le bon ton, meaning ‘good manners’ or ‘good style.’ To be part of the ton was to embody these ideals, demonstrating elegance, wit, and social grace at all times.

The Importance of Reputation

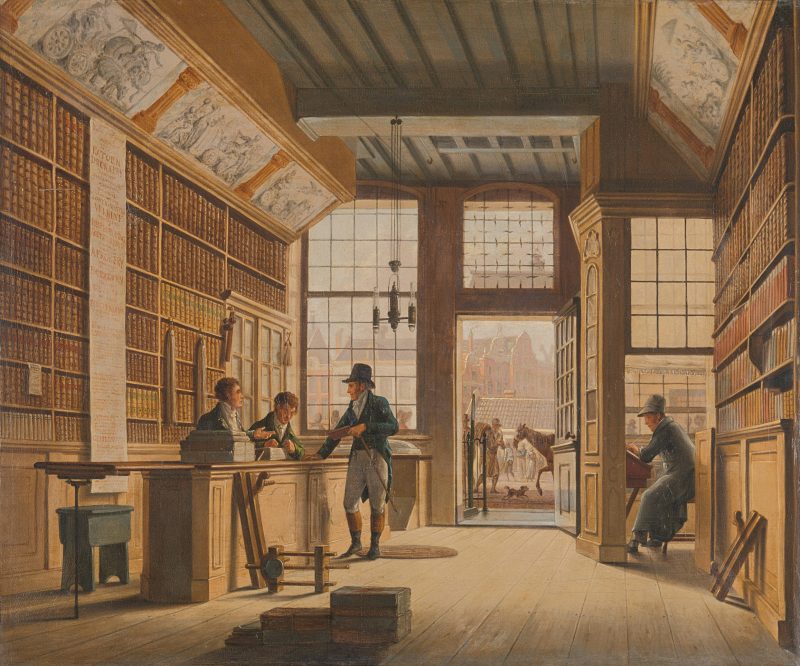

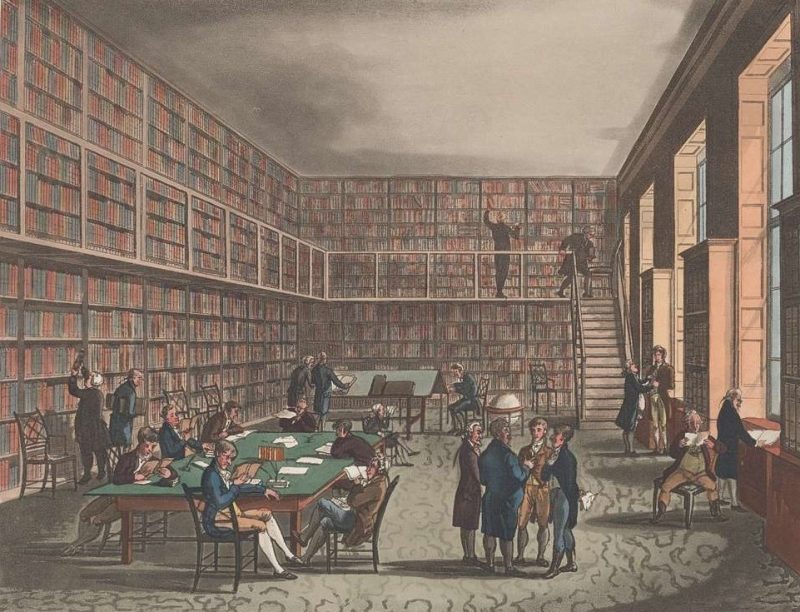

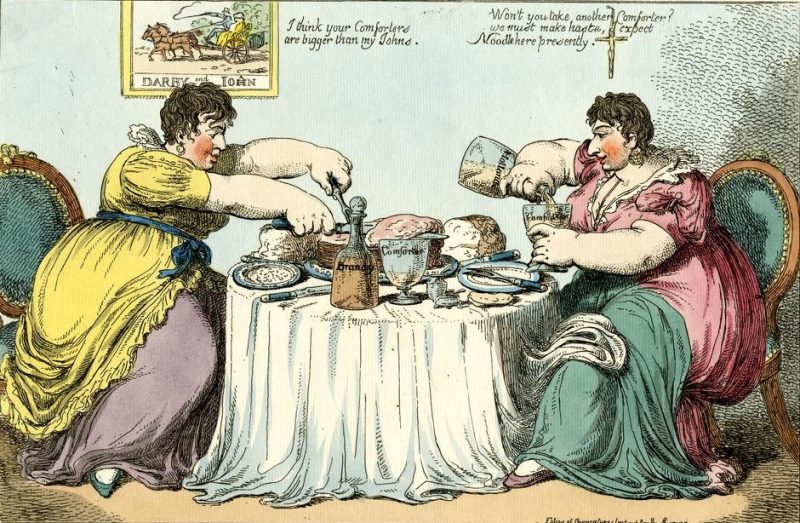

In the ton, reputation was everything. A single scandal—whether real or imagined—could destroy a person’s standing in society. Gossip spread quickly, fuelled by newspapers, letters, and word of mouth. For women, in particular, maintaining a spotless reputation was essential. A hint of impropriety could lead to social ostracism, making it difficult to secure a good marriage or maintain one’s position in society.

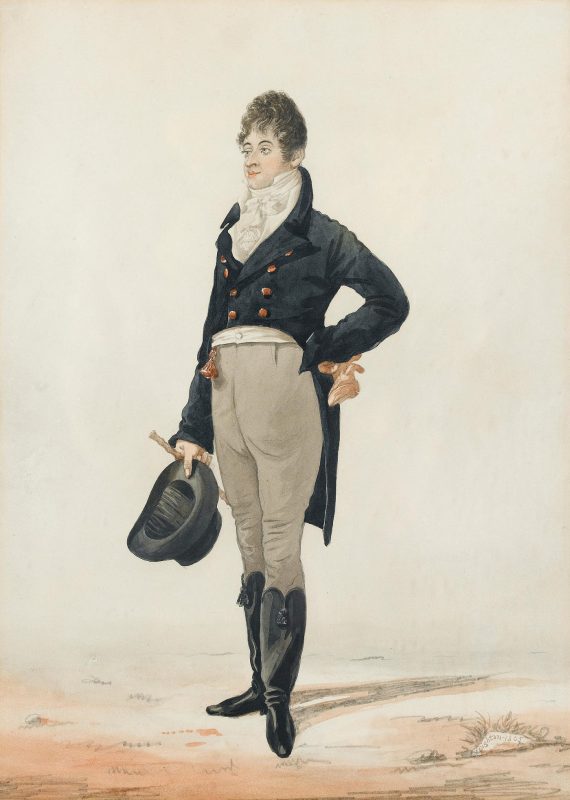

Men were not immune to the pressures of reputation, either. While they had more freedom than women, they were still expected to adhere to codes of honour and conduct. Duels, though illegal, were sometimes fought to defend one’s reputation, particularly in matters of love or insult.

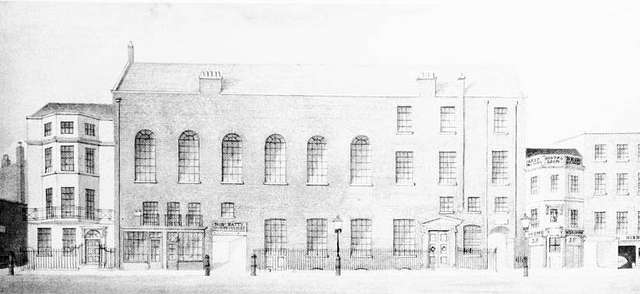

The Role of Almack’s

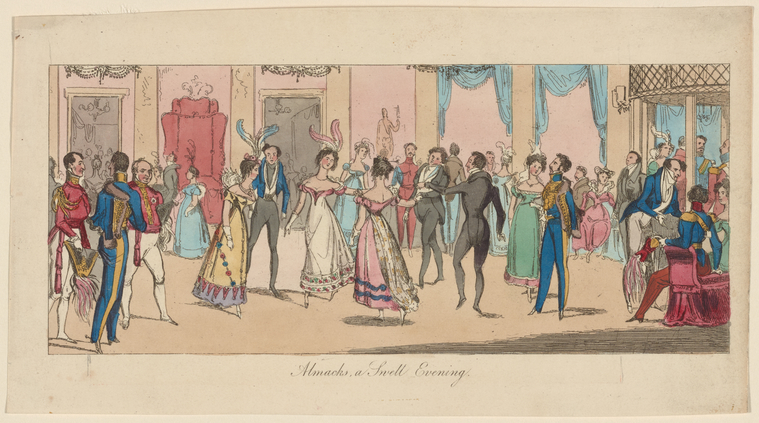

Almack’s Assembly Rooms were the epicentre of the ton. Entry was by voucher only, and the patronesses who controlled access were among the most powerful women in society. Being seen at Almack’s was a mark of social approval, while exclusion was a devastating blow.

The strict rules of Almack’s—such as the requirement to wear knee breeches and the prohibition of waltzing without permission—reflected the ton’s obsession with propriety and exclusivity. Even the Prince Regent himself was once denied entry for failing to meet the dress code.

The Decline of the Ton

By the mid-19th century, the ton began to lose its influence. The rise of the middle class and changes in social norms made the rigid hierarchies of the Regency era seem outdated. However, the legacy of the ton endures in modern concepts of high society and the enduring fascination with aristocracy.

Conclusion

The ton was a world of glittering balls, whispered gossip, and high-stakes social manoeuvring. It represented the pinnacle of Regency society, but it was also a gilded cage, where the pressure to conform and maintain one’s reputation was immense. The ton remains a symbol of the elegance and exclusivity of the era.

References for Further Reading:

- Ton

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ton_(society) - The Ton in Regency England

https://www.historicalemporium.com/blog/2024/05/the-ton-in-regency-england