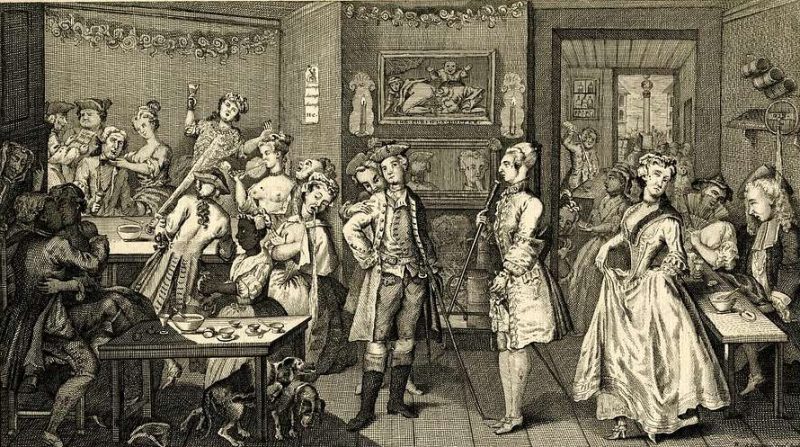

In the Regency era, the coffeehouse was far more than a place to sip a stimulating brew — it was the pulsing heart of public discourse, a stage for gossip, wit, and political posturing. Lively, smoky, and rarely quiet, these establishments became essential fixtures in both London’s tangled streets and the quieter corners of provincial towns. Whether one sought the latest scandal or a spirited exchange on parliamentary reform, the coffeehouse was the place to be.

From Exotic Curiosity to Everyday Essential

Introduced to England in the 17th century via curious merchants and well-travelled diplomats, coffee quickly shed its exotic mystique and found a permanent home in the British routine. By the early 19th century, coffeehouses had evolved into social institutions, offering not only the bitter elixir itself but a generous serving of news, rumour, and opinion — often all in the same conversation.

A Forum for the Informed (and the Ill-Informed)

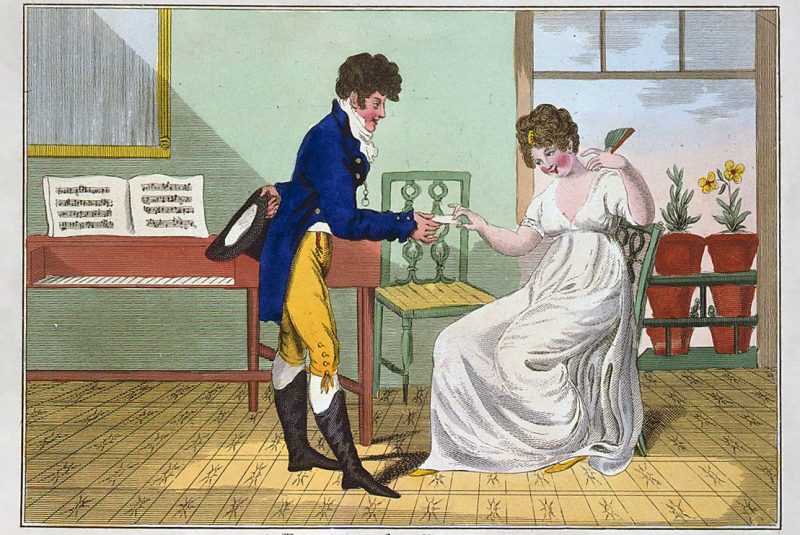

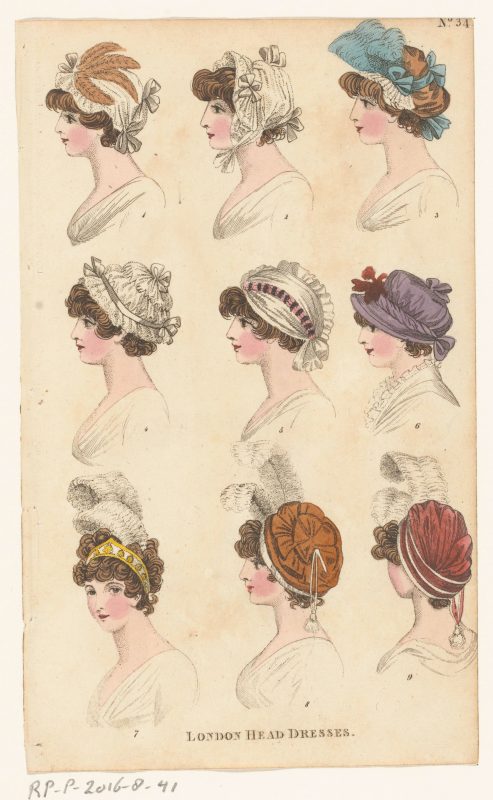

To enter a Regency coffeehouse was to step into a whirlwind of voices. Patrons — from powdered wigs to ink-stained fingers — gathered to read the latest broadsheets, dissect government policy, and theorise wildly about European affairs. The setting was democratic in spirit, if not always in practice. Merchants rubbed elbows with minor gentry; writers and politicians tested their ideas on the listening public. The air was thick with smoke, ambition, and a touch of self-importance.

Coffeehouses also served as informal business hubs, where tradesmen struck deals and ventures were discussed over cups of steaming black coffee. They were, in many ways, precursors to the modern co-working space — though with fewer laptops and more powdered snuff.

Legacy in a Teacup

Though today’s cafes favour laptops and latte art, the soul of the Regency coffeehouse lingers. The tradition of public discourse over a warm drink has not faded — only the surroundings have softened. What began as a cultural import blossomed into a distinctly British institution, one that helped shape both public opinion and private enterprise.

Conclusion

The Regency coffeehouse was more than a gathering place — it was a crucible for conversation, a theatre of ideas, and a haven for those with something (or nothing at all) to say. Its legacy lives on in every spirited debate held over a coffee cup, reminding us that sometimes, history is brewed one conversation at a time.

References for Further Reading:

- Coffee – As Important as Tea

https://shannondonnelly.com/tag/regency-england/ - English Coffeehouses in the 17th and 18th Centuries

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_coffeehouses_in_the_17th_and_18th_centuries - English Coffeehouses, Penny Universities

https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/English-Coffeehouses-Penny-Universities/