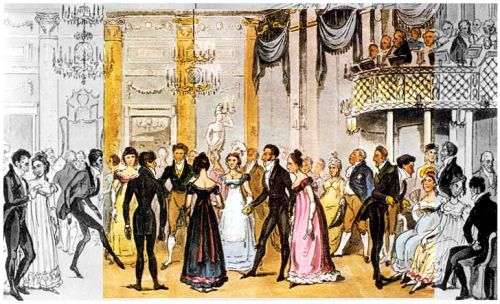

In Regency England, the morning visit was a cornerstone of social interaction, governed by a strict set of rules that dictated when, how, and to whom one could pay a call. These visits were not merely casual drop-ins; they were carefully orchestrated rituals that reinforced social hierarchies and maintained the delicate balance of polite society. For the upper classes, mastering the etiquette of the morning visit was essential to maintaining one’s reputation and social standing.

The Timing of Morning Visits

Morning visits, despite their name, did not take place in the early hours. Instead, they occurred in the late morning or early afternoon, typically between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m. This window allowed ladies and gentlemen to complete their morning routines, such as breakfast and correspondence, before venturing out. Arriving too early or too late was considered a breach of etiquette and could lead to social embarrassment.

The Rules of Engagement

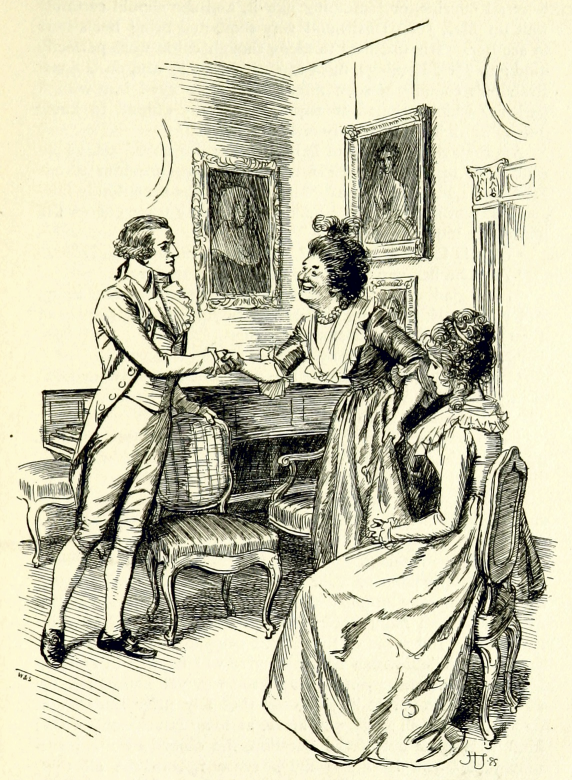

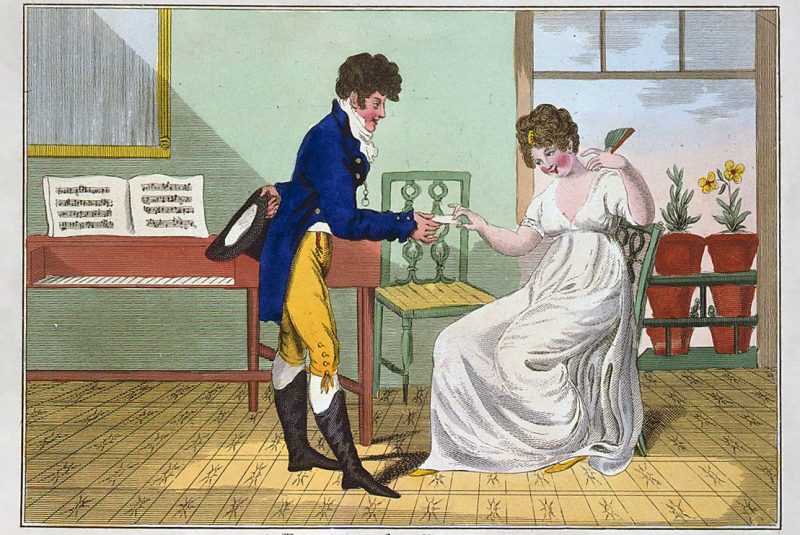

The process of making a morning visit was highly formalised. Upon arriving at a home, visitors would present their calling card to the servant at the door. If the lady of the house was ‘at home’ and willing to receive guests, the visitor would be ushered into the drawing room. Visits were typically short, lasting no more than 15 to 20 minutes, as overstaying one’s welcome was seen as impolite.

The conversation during a morning visit was expected to be light and pleasant, avoiding controversial topics like politics or religion. Compliments on the hostess’ home or appearance were customary, as were inquiries about mutual acquaintances. The goal was to maintain a sense of cordiality and decorum.

The Social Implications

Morning visits were a way to reinforce social connections and demonstrate one’s adherence to societal norms. For women, in particular, these visits were an opportunity to showcase their manners, wit, and social acumen. A well-executed visit could enhance one’s reputation, while a misstep could lead to gossip and social ostracism.

The practice also reflected the rigid gender roles of the time. Women were typically responsible for managing the household’s social calendar, while men’s participation in morning visits was often limited to weekends or special occasions.

The Decline of Morning Visits

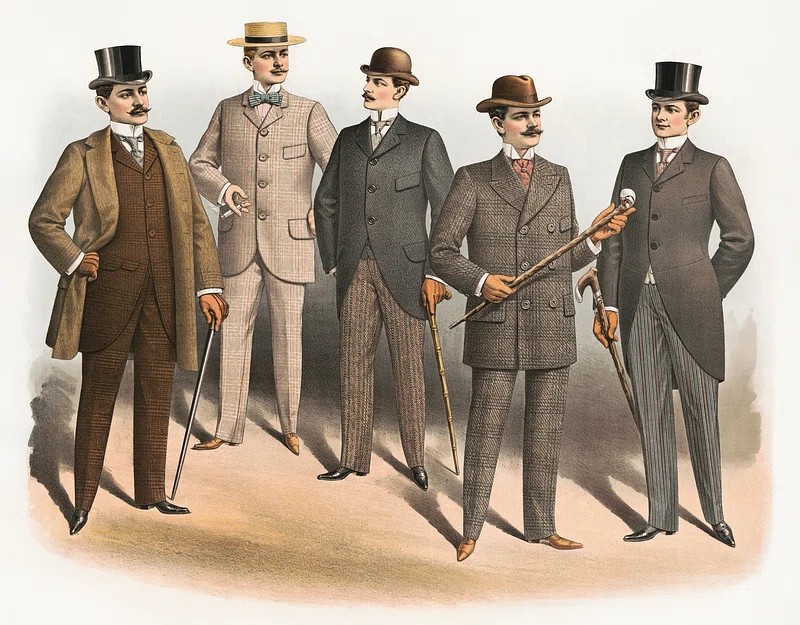

By the mid-19th century, the tradition of morning visits began to decline, as changing social norms and the rise of new forms of entertainment made the practice seem outdated. However, its legacy endures in modern customs like the exchange of business cards and the importance of punctuality in social engagements.

Conclusion

The etiquette of the morning visit offers a fascinating glimpse into the complexities of Regency society. It was a world where even the smallest details—like the timing of a visit or the choice of conversation topics—could have significant social implications. The morning visit remains a symbol of the elegance and formality of the era.

References for Further Reading:

- Morning Calls in the Regency: A Regency History Guide

https://www.regencyhistory.net/blog/morning-calls-regency-history-guide - Paying Social Calls

https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/customs-and-manners/paying-social-calls