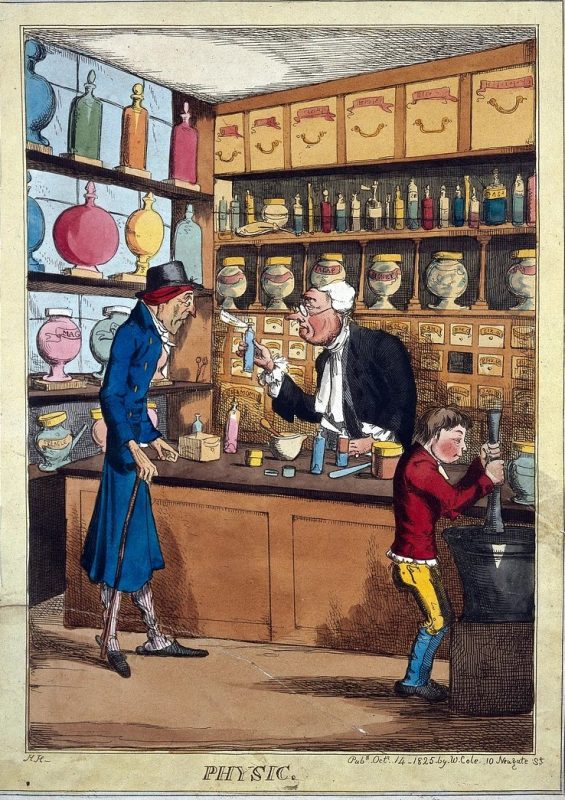

During Regency, apothecary gardens were indispensable to the practice of medicine, serving as living pharmacies where herbs, flowers, and other plants with medicinal properties were cultivated. These gardens, often attached to hospitals, universities, or the estates of wealthy landowners, provided the raw materials for the remedies and treatments that apothecaries and physicians relied upon. At a time when modern pharmaceuticals were nonexistent, apothecary gardens were a cornerstone of healthcare, blending science, tradition, and nature.

The Purpose and Function of Apothecary Gardens

Apothecary gardens were meticulously designed to grow plants used in traditional medicine. Herbs like chamomile, lavender, and peppermint were cultivated for their soothing and antiseptic properties, while more specialised plants, such as foxglove (used to treat heart conditions) and willow bark (a natural source of salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin), were grown for their specific therapeutic benefits. These gardens were not merely practical; they were also centres of learning. Apothecaries, physicians, and students would study the plants, learning how to identify, harvest, and prepare them for use in treatments. The gardens were often organised into neat, labeled beds, making it easy to locate and study each species.

The Layout and Design of Apothecary Gardens

The design of an apothecary garden reflected both its practical purpose and the aesthetic sensibilities of the era. Plants were typically arranged in geometric patterns, with each bed dedicated to a specific type of herb or flower. Labels provided information about the plant’s name, properties, and uses. Some gardens also included greenhouses or hothouses to cultivate exotic species that required warmer climates. The gardens were often enclosed by walls or hedges, creating a serene and controlled environment that protected the plants from pests and harsh weather.

The Social and Scientific Significance

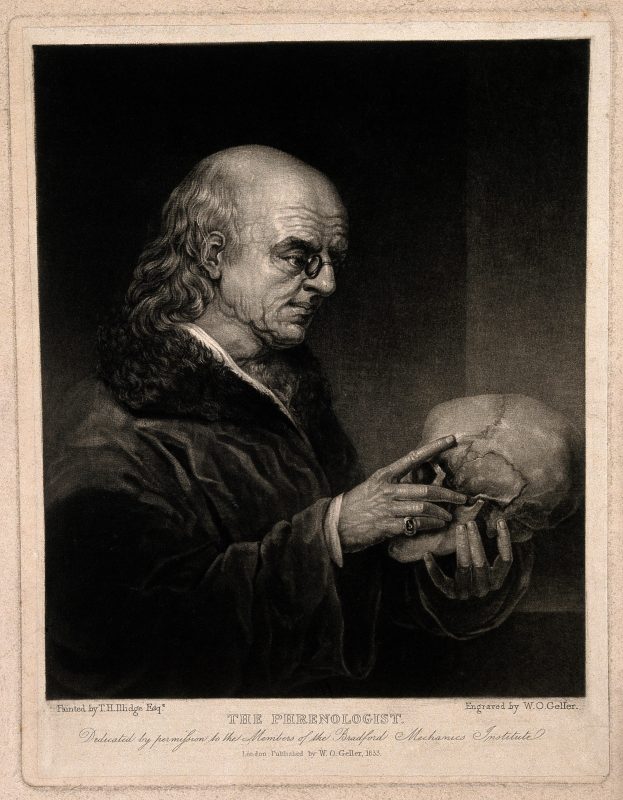

Apothecary gardens were more than just sources of medicine; they were symbols of the growing interest in botany and natural science during the Regency era. The study of medicinal plants was closely tied to the broader Enlightenment ideals of observation, experimentation, and the pursuit of knowledge. Wealthy landowners often maintained private apothecary gardens as a mark of their sophistication and commitment to health and well-being. Public gardens, such as those attached to hospitals, played a vital role in community healthcare, providing remedies for common ailments and injuries.

The Legacy of Apothecary Gardens

While modern medicine has largely replaced the use of herbal remedies, apothecary gardens remain a testament to the close relationship between nature and healing. Many historic gardens, such as the Chelsea Physic Garden in London, have been preserved as living museums, offering a glimpse into the medicinal practices of the past. Today, there is a renewed interest in the therapeutic properties of plants, as people seek natural alternatives to synthetic drugs. The legacy of the Regency apothecary garden endures in the continued use of medicinal plants and the preservation of these historic spaces.

Conclusion

The Regency apothecary garden was a vital resource in an era when healthcare relied heavily on natural remedies. It reflected the era’s fascination with science and nature, as well as its commitment to improving health and well-being. The legacy of these gardens lives on in the continued study and use of medicinal plants, reminding us of the enduring connection between humans and the natural world.

References for Further Reading:

- Welcome To The Poison Garden: Medicine’s Medieval Roots

https://www.ijpr.org/2019-07-08/welcome-to-the-poison-garden-medicines-medieval-roots - What to grow in a medieval herb garden

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/blog/blog-posts/grow-medieval-herb-garden/